|

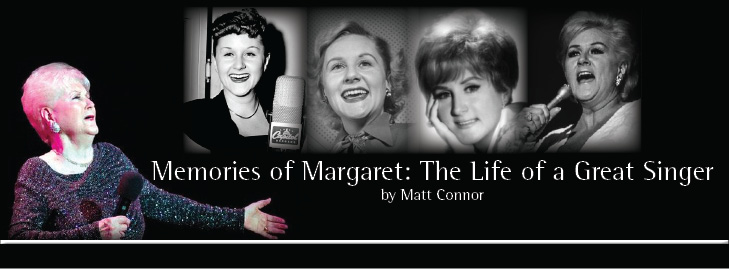

If it hadn't been for a crazy, long-haired runner from Lock Haven University

in the 1980s, I might never had had a chance to form a warm, decades-long,

on-and-off acquaintanceship with music legend Margaret Whiting, who passed away

January 10, 2011 at age 86. If it hadn't been for a crazy, long-haired runner from Lock Haven University

in the 1980s, I might never had had a chance to form a warm, decades-long,

on-and-off acquaintanceship with music legend Margaret Whiting, who passed away

January 10, 2011 at age 86.

Maggie, as she was affectionately known in the show business world, was a top

recording star in the post-World War II era, with million-selling records like

"Moonlight in Vermont," "It Might As Well Be Spring" and my personal favorite,

"My Ideal." She remained active long after her last hits dropped off the

Billboard charts in the 1960s, performing in nightclubs and theaters, on TV

specials and hosting workshops for young musicians until, in her final years,

health problems finally curtailed her activities.

It was an odd Lock Haven incident that kicked off the first of a long series

of conversations with Maggie over the phone, and a few fleeting meetings with

her during the last decade of her life.

It all started with a Rebecca Gross Day at LHU in the early 1990s. At that

time I met up with an old friend and visiting LHU alum, Andy Shearer, the

aforementioned long-haired runner, with whom I had been friendly during our

undergraduate days. By then Andy was the manager of a Philadelphia radio station

that specialized in Big Band music, and I pitched a show to Andy in which I

would interview old time music stars, interspersed with bits of the stars'

hits.

One of the first stars with which I landed an interview was Margaret Whiting,

who delighted me with her sharp and funny anecdotes about the music business.

Her father, Richard Whiting, had been one of the great songwriters of the Golden

Age of Hollywood. Among other tunes, he wrote "Hooray for Hollywood" and, for

film star Shirley Temple, "The Good Ship Lollipop."

That song, by the way, was inspired by Margaret, who as a tiny little girl

climbed on her father's lap while he was trying to compose on the piano. She had

a huge lollypop in her hand and ended up getting sticky stuff all over the sheet

music, frustrating her dad until finally inspiration struck: That's it, he

thought, he'd write a song about lollipops!

Margaret told me during her childhood, her home in Beverly Hills was

constantly filled with artistic, creative people. Folks like Cole Porter and

Judy Garland would stop by for visits and hang around at the piano singing and

playing their latest tunes. It must have been incredible.

"We'd sit with Dick Rogers and Larry Hart and some of these great songwriters

and then they'd go in and play and there was no escaping for me," Margaret told

me during one of our telephone conversations. "That was it."

Stories like that absolutely astounded me. The fact that she talked about men

like Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart on a first-name basis - these being the

authors of such classics as "The Lady is a Tramp," "My Funny Valentine" and "My

Heart Stood Still" just blew me away.

"It really was a great thing for me," she said. "I remember one day when I

came home from school, this was in Holmby Hills, next to Bel Air, and I said,

'Where's Daddy?' Well, he was down playing golf at the little pitch and putt

golf course about two blocks from us.

"If any of these songwriters were working at the Hollywood studios, they

loved to play golf when they were writing. They'd play their songs for Daddy and

they'd have wonderful creative people who could judge them and tell them, 'Oh,

my God, that's a gorgeous song' you know. The masters of songwriting would all

come over, they'd have a drink, they'd have lunch, they'd go down and play golf,

they'd come back and have another drink and play the songs and have a wonderful

time.

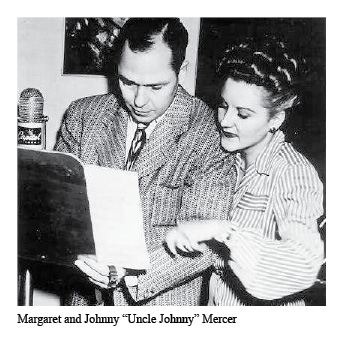

"So on this day I came home from school and was told my father was playing

golf, and I decided to go down there. I took my bike - it was only two blocks -

and I found him with five different men, all of whom I knew. I said, 'Hello

Uncle Johnny.' That was Johnny Mercer. 'Hello Uncle Harry.' That was Harry

Warren. 'Hello Uncle Harold.' That was Harold Arlen. And then there was one man,

much older than the rest of these people, who was kind of smiling about all

this.

"And this man said, 'I've heard about you, Margaret. I hear you're going to

be a wonderful lady and I've been anxious to meet you. I long for the day when

you can call me Uncle Jerry. But right now I'm just Jerome Kern.

"So I said, 'Gee, you're my father's favorite composer!' And the other three

chimed in with, 'OUR favorite composer!'"

It took me days to recover from that story. Imagine a casual grouping of the

greatest popular songwriters of all time gathered in one spot, trading quips

with an tiny little girl who would herself grow up to become a music legend.

Just a quick refresher, for those who might not be familiar with Margaret's

myriad golf-playing "uncles." If all Harry Warren ever did with his life was

write the gorgeous, "You'll Never Know," he would have left the world a much

better place. But he also wrote countless other hits including "The More I See

You" and a particular favorite of our current president, "At Last," which was

played over and over during the Obama inauguration balls. Just a quick refresher, for those who might not be familiar with Margaret's

myriad golf-playing "uncles." If all Harry Warren ever did with his life was

write the gorgeous, "You'll Never Know," he would have left the world a much

better place. But he also wrote countless other hits including "The More I See

You" and a particular favorite of our current president, "At Last," which was

played over and over during the Obama inauguration balls.

Johnny Mercer wrote "Skylark," "Laura," "Moon River" and "Midnight Sun."

Harold Arlen wrote the immortal "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" and "The Man

that Got Away."

Jerome Kern? "A Fine Romance." "The Way You Look Tonight." "All the Things

You Are."

My first interview with Margaret went very well. In fact we hit it off so

well that she invited me to attend an event she was hosting at the Bucks County

Playhouse later that week, an engagement I had to skip because I had already

RSVP'd to a party for guitar god Les Paul at Manhattan's Iridium Nightclub on

the same night. I lived kind of a glamorous life in those long-ago days.

In any case, Philly radio station manager Andy Shearer and I were making

arrangements to air the interviews with Margaret and other musical stars of that

era when the station was suddenly bought by Disney and changed format. My shows

about old music stars were permanently shelved.

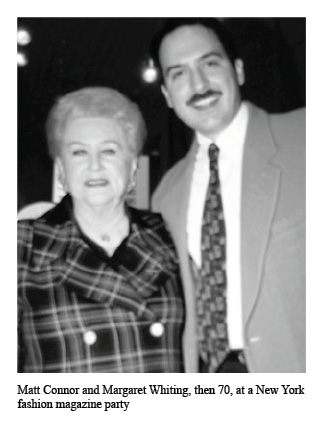

Then in 1995 I was at a party in New York celebrating the launch of a now

defunct fashion magazine when I looked up and there, standing across the room in

tasteful plaid, was Margaret Whiting.

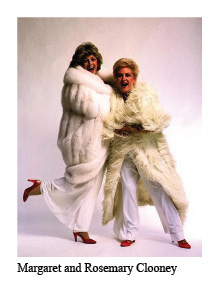

I walked over and said hello and told her I was planning on soon seeing a

mutual friend - the singer Rosemary Clooney - in concert. I walked over and said hello and told her I was planning on soon seeing a

mutual friend - the singer Rosemary Clooney - in concert.

"Tell her I'll be in to see her soon," Margaret said of Rosemary. "I always

go to see her when she's in New York." Whiting and Clooney spent years

performing together in an act called "Four Girls Four" with big band singer

Helen O'Connell, the Dick Van Dyke Show star Rose Marie and a host of other

singer-comediennes.

Happily, a photographer was present to snap a photo of the Margaret and me

together.

I liked Margaret especially well, and rang her phone number whenever I could

come up with a reason to do another story about her, which happened about a

half-dozen times over the course of the next 10 years.

At one point I was doing some freelance work for a magazine called "Out in

Jersey" and they wanted celebrity quotes on the most romantic songs of all time

for a Valentine's issue. I called Maggie about that one, and her answer was

Roger's and Hart's "My Romance."

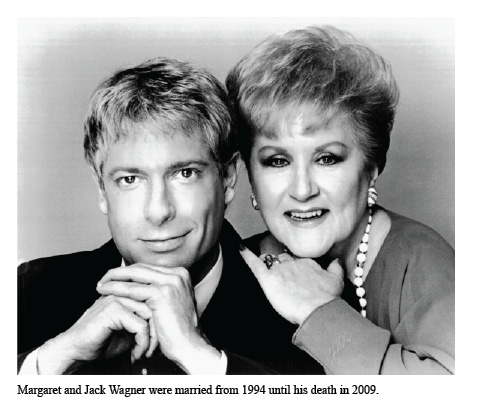

In the 1970s, Margaret set tongues wagging when she entered into a rather

unconventional romantic relationship with a fellow named Jack Wrangler, then the

number one gay porn star in America. Indeed, I once asked her if she'd let me

interview her about her relationship with Wrangler, but she turned me down about

that one. It was just a little too personal, I think. In the 1970s, Margaret set tongues wagging when she entered into a rather

unconventional romantic relationship with a fellow named Jack Wrangler, then the

number one gay porn star in America. Indeed, I once asked her if she'd let me

interview her about her relationship with Wrangler, but she turned me down about

that one. It was just a little too personal, I think.

Over a decade later both Jack and Maggie participated in filmmaker Jeffrey

Schwarz's terrific documentary, "Wrangler: Anatomy of an Icon," which is

surprisingly tasteful despite the subject matter.

In 2003 and 2004 I began writing and researching a long article for an

Internet website on the aforementioned Four Girls Four nightclub act. I had

several conversations with Margaret for that story, and after it was published,

Margaret and I spoke on the phone again and she shared a few further details

about Rosemary Clooney and the other ladies in the act that never saw print

until now.

"When we started, we had a young boy who drove us around, Rosemary did,"

Margaret said slyly. "He's grown up now. He's doing pictures. Maybe you know

him, George Clooney? He drove us around. At least he drove Rosemary and myself

around. I don't know how the other girls got around. He was a beautiful

kid."

Did she have any idea at the time that this young kid would someday be a

huge, Oscar-winning film personality?

"No," she said. "No, no, no. I knew he was hip, because he was connected to

that family. I had met his father, Nick, who was a great reporter in Cincinnati. He

had a TV program and I was on it. And George is like his father. He has such

belief in the world and knows it's in such trouble and wants to help the

countries of Africa. They're in such a mess, you know?

"He did a movie about one of my favorite people who I was fortunate enough to

know, being in the business: Edward R. Murrow. Murrow and I shared two programs

on CBS. I was on with Bob Crosby and his orchestra and the Andrews Sisters and

we had a wonderful time singing with the band and everything. Then at 6:15 or

6:30 Murrow would go on from Philadelphia with a program about world issues. He

was such a wonderful speaker.

"I was invited to Washington for a party hosted by the president, and he

went, too. He picked me up in the CBS plane in New York and flew me to

Washington, where he dropped me off. So I went to the hotel and didn't see him

after that till I was walking up the steps of the White House and I heard this

voice say, 'Hello, Maggie. It's me, Edward R.'

"Later I did something with the CBS sponsors and I got to know Edward R.

Murrow very well, and I thought it was so wonderful for George to do that

picture."

"That picture," was "Good Night and Good Luck," the story of pioneering TV

journalist Murrow's battles with Sen. Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s. It was

nominated for six Academy Awards in 2005, including for George Clooney's

direction.

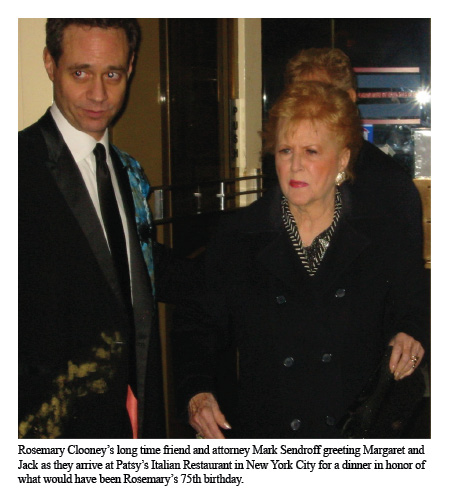

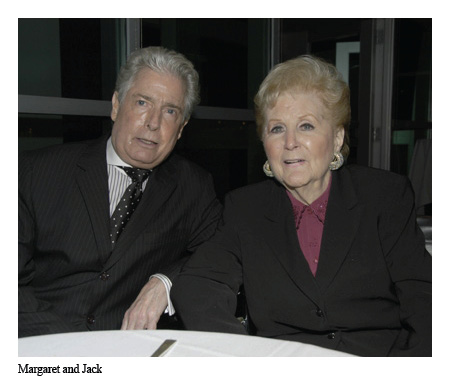

The last time I saw Margaret in person was at Patsy's Italian restaurant in

New York City, where there was a memorial dinner for Rosemary Clooney. She

attended with Wrangler, who I had never met or spoken with, so I was a bit leery

about approaching her table. The last time I saw Margaret in person was at Patsy's Italian restaurant in

New York City, where there was a memorial dinner for Rosemary Clooney. She

attended with Wrangler, who I had never met or spoken with, so I was a bit leery

about approaching her table.

"When Rosemary died they had a party for all of her friends here in New York,

at Patsy's, where I guess you and I passed in the night," Margaret said with a

laugh during a conversation I had with her in 2006. "But it was so wonderful to

see George's father there, and how much George is like his father. What a great

family. Nick was talking about Rosemary and he said she had died with

passion and goodness. It was really wonderful. Rosemary and I were very close.

She used to say I reminded her of her sister, Betty."

At which point we both got a little choked up. Betty and Rosemary Clooney

were a particularly close singing duo in the late 1940s. They later recorded the

hit record "Sisters" together, but Rosemary never really got over Betty's death

from a brain aneurysm in 1976.

I changed the subject and we talked a little about Wrangler, for the first

time. Given his more colorful career before he met Margaret, I was impressed, I

told her, with how much she stuck by him. She has written that she believed he

was capable of more than mere pornographic movies, that he could be a great

writer and stage producer.

"Some people dug him right away and saw what I saw in him, but he certainly

proved himself to people," she said. "Being in a relationship takes guts, you

know. It takes knowledge. It takes humor, but when you know that someone has

that talent and can do things like that, I just said, 'Let me show you what you

should be.' But he was on his way out of the other thing (pornography)

anyway."

Did she feel he was exploited during his years in gay porn?

"No," she said, somewhat surprisingly, and described a party she once

attended that apparently was largely populated by Wranger's co-stars and

colleagues from that industry.

"When I met them, and I went to the first gorgeous party, it was so different

than what I imagined. They were men and women that came from the industry and

they were directors and producers that had done big pictures, and it was very

much on one level that they were going to do something that was a little

different, but they did it with taste and they did it with their ability. You'd

be surprised the people that were in that group. They were professionals.

"We don't worry about any of that, now," she said, and with that the subject

seemed to be closed.

It was at about that same time that I talked to her about coming to Lock

Haven and to hold a kind of master class for LHU music students. It had already

been cleared by one of my professor friends in the university Arts department,

so I simply picked up the phone and asked her.

She demurred, saying she was too busy writing the second volume of her

memoirs and performing at the 92nd Street Y, one of the great performance spaces

in New York City. But I suspect her health was already troubling her and that

she worried about the four-hour drive out to Clinton County.

But she promised to take me out to lunch the next time I was in New York

City. And when we next spoke on the phone, in 2006, for a radio interview

program I had launched here in Lock Haven, she reminded me of the earlier lunch

invitation.

"Will you call me the next time you're in New York?" she asked.

"Probably not," I said with a laugh. "Probably not," I said with a laugh.

"Why not?" she asked.

"Because you're Margaret Whiting and I'm just some schmuck from New Jersey,

that's why!"

"Now please don't be like that," she scolded. "Promise you'll call me next

time you're in New York."

But I never did. And it was pretty rare that I got into New York by then,

anyway.

Sadly, Jack Wrangler died in 2009 at age 62, leaving Margaret somewhat

rudderless. He was always a heavy smoker and emphysema was what got him in the

end. Margaret was bereft.

I spoke with her after Jack died, and she cried frequently when talking about

Rosemary ("She was my girlfriend... I still miss her so...") and particularly

about Jack: "My husband died three weeks ago," she said through copious

tears.

"I know. I know, dear," I told her.

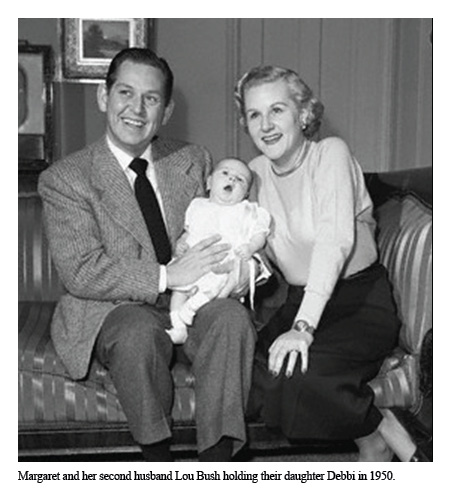

After Margaret's death at age 86 last month, I left a message on the

voicemail for her old telephone number in New York, asking where I should send a

sympathy note to her daughter, Debbi. A few days later, Debbi phoned me in

person. After Margaret's death at age 86 last month, I left a message on the

voicemail for her old telephone number in New York, asking where I should send a

sympathy note to her daughter, Debbi. A few days later, Debbi phoned me in

person.

We spoke at some length about her mother's last years. For example, by the

time the documentary about Wrangler came out in 2008, she said, both Jack and

Margaret were already too ill to attend the premier.

During her last weeks in her New York apartment, Margaret rarely went out,

Debbi said, and she grew bored watching the same old movies on TV. She longed

for companionship, so she was very sincere, Debbi said, when she had asked me

repeatedly to come visit her in New York. She would have loved to have had

someone new to talk to.

It made me feel doubly sad, not just for the loss of this great lady, but for

the opportunity I had missed to spend some more time with her. Matt Connor can be reached at mbconnor4265@gmail.com. This article

originally appeared in Lockhaven's The Express on

February 19, 2011.

|